Wine Making April 1st, 2018

Wine Making

Grapes are the world’s leading fruit crop and the eighth most important food crop in the world, exceeded only by the principal cereals and starchytubers. Though substantial quantities are used for fresh fruit, raisins, juice and preserves, most of the world’s annual production of about 60 million metric tons is used for dry (nonsweet) wine.

Wine is of great antiquity, as every Bible reader knows, and a traditional and important element in the daily fare of millions. Used in moderation, it is wholesome and nourishing, and gives zest to the simplest diet. It is a source of a broad range of essential minerals, some vitamins, and easily assimilated calories provided by its moderate alcoholic content.

In its beginnings, winemaking was as much a domestic art as bread making and cheese making. It still is, wherever grapes are grown in substantial quantity. Though much wine is now produced industrially, many of the world’s most famous wines are still made on what amounts to a family scale, the grape grower being the winemaker as well.

Production of good dry table wine for family use is not difficult, provided certain essential rules are observed.

The right grapes.

Quality of a wine depends first of all on the grapes it is made from. As is true of other fruits, there are hundreds of grape varieties. They fall in three main groups.

- First, there are the classic vinifera wine grapes of Europe. These also dominate the vineyards of California, with its essentially Mediterranean climate. But several centuries of trial have shown that they are not at home in most other parts of the United States.

- Second, there are the traditional American sorts such as Concord, Catawba, Delaware, and Niagara, which are descendants of our wild grapes and much grown where the vinifera fail. They have pronounced aromas and flavors, often called foxy, which, though relished in the fresh state by many, reduce their value for wine.

- Third, there are the French or French-American hybrids, introduced in recent years and now superseding the traditional American sorts for winemaking. The object in breeding these was to combine fruit resembling the European wine grapes with vines having the winter hardiness and disease resistance of the American parent. They may be grown for winemaking where the pure European wine grapes will not succeed.

What wine is.

Simply described, wine is the product of the fermentation of sound, ripe grapes. If a quantity of grapes is crushed into an open half-barrel or other suitable vessel, and covered, the phenomenon of fermentation will be noticeable within a day or two, depending on the ambient temperature. It is initiated by the yeasts naturally present on the grapes, which begin to multiply prodigiously once the grapes are crushed.

Fermentation continues for three to ten days, throwing off gas and a vinous odor. In the process, the sugar of the grapes is reduced to approximately half alcohol and half carbon dioxide gas, which escapes. Fermentation subsides when all the sugar has been used up. The murky liquid is then drained and pressed from the solid matter and allowed to settle and clear in a closed container. The resulting liquid is wine-not very good wine if the constituents of the grapes were not in balance, and readily spoiled, but wine nevertheless.

Beneath the apparent simplicity, the evolution of grapes into wine is a series of complex biochemical reactions. Thus winemaking can be as simple or as complex as you wish to make it. The more you understand and control the process, the better the wine.

The following instructions cover only the essentials of sound home winemaking. Under Federal law the head of a household may make up to 200 gallons of wine a year for family use, but is first required to notify the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms on Form 1541.

Making Red Wine

The grape constituents which matter most to the winemaker are (a) sugar content of the juice, and (b) tartness or “total acidity” of the juice. Sugar content is important because the amount of sugar determines alcoholic content of the finished wine.

A sound table wine contains between 10% and 12% alcohol. The working rule is that 2% sugar yields 1% of alcohol. Example: a sugar content of 22% yields a wine of approximately 11 % alcohol.

California grapes normally contain sufficient sugar. Grapes grown elsewhere are often somewhat deficient, and the difference must be made up by adding the appropriate amount of ordinary granulated sugar which promptly converts to grape sugar on contact with the juice.

Sugar Correction Table

| What the saccharometer shows |

For wine of 10% by volume. add |

For wine of 12% by volume, add |

|

Ounces of sugar per gallon |

| 10 |

11.8 |

16.2 |

| 11 |

10.1 |

14.8 |

| 12 |

8.9 |

13.3 |

| 13 |

7.4 |

11.9 |

| 14 |

5.9 |

10.4 |

| 15 |

4.6 |

8.9 |

| 16 |

3.0 |

7.5 |

| 17 |

1.5 |

6.0 |

| 18 |

|

4.3 |

| 19 |

|

2.9 |

| 20 |

|

1.4

|

| Note: The result is not precise. yield of alcohol varying under the conditions of fermentation. Adapted from Grapes Into Wine by Philip M. Wagner. |

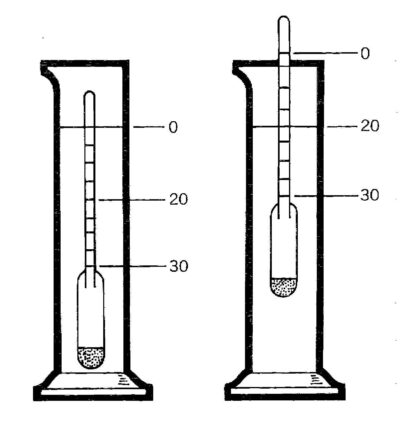

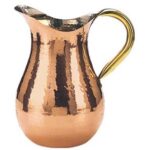

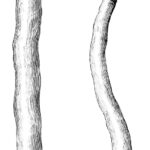

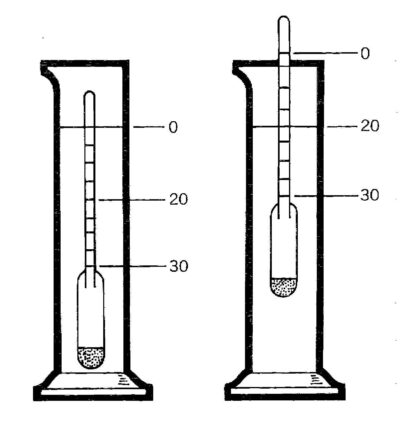

Saccharometer and hydrometer jar. Instrument floats at zero in plain water. It floats higher according to sugar content of grape juice.

1.4

Note: The result is not precise. yield of alcohol varying under the conditions of fermentation.

-Adapted from Grapes Into Wine by Philip M. Wagner.

In using non-California grapes, you need to test the sugar content in advance. That is done by a simple little instrument called a saccharometer, obtainable at any winemakers’ shop. This is floated in a sample of the juice, and a direct reading of sugar content is taken from the scale. The correct amount of sugar to add, in ounces per gallon of juice, is then determined by reference to the sugar table.

If total acidity, or tartness, is too high and not corrected, the resulting wine will be too tart to be agreeable. Again, California grapes are usually within a satisfactory range of total acidity. Grapes grown elsewhere are often too tart, and acidity of the juice should be reduced.

In commercial winemaking this is done with precision. The home winemaker rarely makes the chemical test for total acidity but uses a rule of thumb. He corrects the assumed excess of acidity with a sugar solution consisting of 2 pounds of sugar to 1 gallon of water- adding 1 gallon of the sugar solution for every estimated 4 gallons of juice. This sugar solution is in addition to the sugar required to adjust sugar content of the juice itself.

In estimating the quantity of juice, another practical rule is that 1 full bushel of grapes will yield approximately 4 gallons. The winemaker therefore corrects with 1 gallon of sugar solution for each full bushel of crushed grapes.

The pigment of grapes is lodged almost entirely in the skins. It is during fermentation “on the skins” that the pigment is extracted and gives red wine its color.

How to proceed. Crush the grapes directly into your fermenter (a clean open barrel, plastic tub or large crock, never metal). Small hand crushers are available, but the grapes may be crushed as effectively by foot – wearing a clean rubber boot. Then remove a portion of the stems, which may otherwise give too much astringency to the wine.

Low-acid California grapes are quite vulnerable to bacterial spoilage during fermentation. To prevent spoilage and assure clean fermentation, dissolve a bit of potassium metabisulfite (known as “meta” and available at all winemakers’ shops) and mix it into the crushed mass. Use ¼ ounce (⅓ of a teaspoonful) per 100 pounds of grapes.

Also use a yeast “starter”. This comes as a 5 gram envelope of dehydrated wine yeast, also obtainable at winemakers’ shops. To prepare the starter, empty the granules of yeast into a shallow cup and add a few ounces of warm water. When all the water is taken up, bring it to the consistency of cream by adding a bit more water. Let stand for an hour, then mix it into the crushed grapes.

After the meta and yeast are added, cover the fermenter with cloth or plastic sheeting to keep out dust and fruit flies, and wait for fermentation. If non-California grapes are used, test and make the proper correction for sugar content. Then correct the total acidity by adding sugar solution as described earlier. In using non California grapes, it is desirable, but not necessary at this point, to add a dose of meta. A yeast starter is advisable.

As fermentation begins, the solid matter of the grapes will rise to form a “cap”. Push this down and mix with the juice twice a day during fermentation, always replacing the cover. When fermentation begins to subside and the juice has lost most of its sweetness, it is time to separate the turbid, yeasty and rough-tasting new wine from the solid matter. For this purpose a press is necessary, preferably a small basket press though substitutes can be devised.

Be ready with clean storage containers for the new wine, several plastic buckets, and a plastic funnel. The best storage containers for home winemaking are 5-gallon glass bottles or small fiberglass tanks.

Beware of small casks and barrels for several reasons. They are usually leaky. They are sources of infection and off-odors that spoil more homemade wine than any other one thing. And there is frequently not enough new wine to fill and keep them full. Wine containers must be kept full; otherwise the wine quickly spoils. Using glass containers, you can see what you are doing.

With the equipment assembled, simply bail the mixture of juice and solid matter into the press basket. The press basket serves as a drain, most of the new wine gushing into the waiting buckets and being poured from them into the containers. When the mass has yielded all its “free run”, press the remainder for what it still contains.

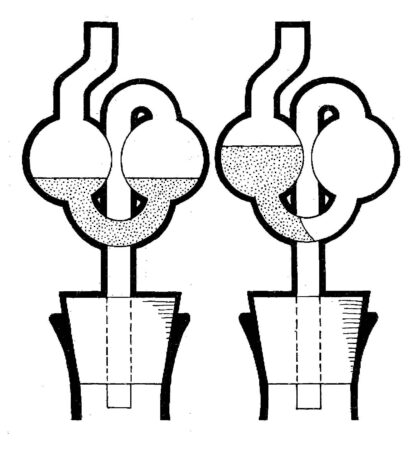

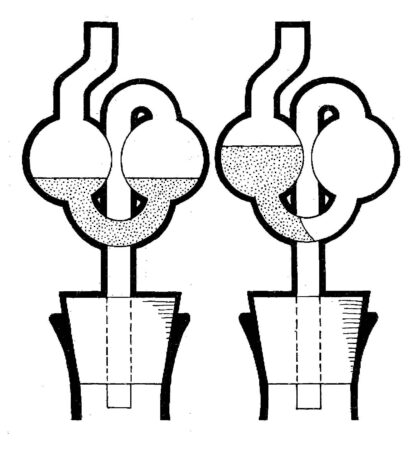

Fill the containers full, right into the neck. Since fermentation will continue for awhile longer, use a stopper with a fermentation “bubbler” which lets the gas out but does not let air in. When the bubbler stops bubbling and there are no further signs of fermentation, replace it with a rubber stopper or a cork wrapped in waxed paper.

Store the wine for several weeks at a temperature of around 60° F. Suspended matter in the wine will begin to settle, and at this temperature certain desirable reactions continue to take place in the wine itself.

At the end of this period, siphon the wine from its sediment, with a plastic or rubber tube into clean containers.

At the same time dissolve and add a bit of the meta already referred to at the rate of ¼ level teaspoon per 5 gallons of wine. This will protect against off odors and spoilage but does not otherwise affect the wine.

Clarifying.

Next, transfer the containers to a place where the wine will be thoroughly chilled, even down to freezing. This precipitates more suspended matter and unwanted ingredients, and encourages clarification.

Assuming that the wine was made in early fall, hold it in cool storage until after the first of the year. By then it should have “fallen bright” and be stable. To test its clarity, hold a lighted match behind the bottle. The wine is then siphoned once again from its sediment, and dose of meta added at the same rate of ¼ teaspoon per 5 gallons.

If the wine is brilliantly clear, one container of it may then be siphoned into wine bottles, corked or capped, and is ready for immediate use. Despite the common impression, most wine does not gain greatly by aging once it is stable. It continues to evolve, but not necessarily for the better.

The rest of the wine is held until after the return of warm weather to make sure there will be no resumption of fermentation, which would blow corks if the wine was bottled. By mid-May that hazard will have passed, and the wine is ready for its final siphoning, its final dose of the same quantity of meta, and bottling.

Fining.

If in January the wine is not brilliantly clear, it should be “fined”. This consists of dissolving in a small amount of hot water and mixing in, at the time of siphoning, ordinary household gelatin at the rate of ¼ ounce (2 teaspoonsful) per 5 gallons. This will turn the wine milky when mixed in and will slowly settle, dragging all impurities and suspended matter with it. In two weeks to a month the process of “fining” will be complete. The wine is then ready to be siphoned from the fining sediment and treated as above.

Making White Wine

As we have seen, red wine is fermented “on the skins” in order to extract the coloring matter and other ingredients lodged in the skins. In making white wine, the grapes are crushed and the fresh juice immediately separated by pressing so that it may ferment apart from the skins.

This fresh juice is checked for its sugar content and acidity, as in preparing to ferment red wine, and the proper corrections are made immediately after pressing. Likewise, a yeast “starter” is added.

The fermentation takes place in the same 5-gallon glass containers that are later used for storage. But as fermenters they are filled only two thirds full as a precaution against any overflow or unmanageable formation of bubbles. When the primary fermentation has run its course, the several partly filled bottles are simply consolidated—filled full and equipped with bubblers.

Subsequent siphoning from sediment, chilling, and dosing with meta are carried out as with red wine. If fining is necessary, it differs in one respect: before mixing in the gelatin, mix in an equal amount of dissolved tannic acid to remove the impurities. Tannic acid is obtainable at drug stores or winemakers’ shops as a powder. This provides better settling out of suspended matter.

Dry table wine is a food beverage, to be used with meals. Sweet wines are more like cordials. The making of sweet wines takes advantage of a characteristic of the yeast organism, namely, that its activity dies down and it usually ceases to ferment sugar into alcohol after a fermenting liquid reaches an alcoholic content of around 13%.

The secret, then, is to add an excess of sugar when correcting the juice of crushed grapes before fermentation. When fermentation ceases, there is still some residual sugar in the juice.

From then on the still-sweet new wine is treated much as other wine.

The three important differences are:

- the wine is siphoned from its sediment immediately after fermentation, without the waiting period at 60° F;

- the chilling begins as soon as possible; and

- the dose of meta added then and at each subsequent siphoning is doubled (½ teaspoon per 5 gallons instead of ¼ teaspoon) to guard against spoilage and against any accidental resumption of fermentation.

Sweet Wine Making

| Fruit |

Average sugar level |

Sugar needed per gallon to make a sweet wine |

Average Acid |

Gallons of sugar water to add per gallon |

| Grapes [eastern] |

12-20 |

1 ¼-2 |

med. To high |

0-1 |

| Grapes [Calif.] |

16-20 |

1-1 ½ |

low² to high |

0 |

| Apples |

13 |

2-2 ½ |

low² to high |

0-1/2 |

| Apricots |

12 |

2-2 ½ |

med. to high |

0-1/4 |

| Blackberries |

6 |

2-3 |

high to very high |

1 or more |

| Blueberries |

8 |

2 ¼-3 |

low to med. |

0 |

| Cherries[sour] |

14 |

2-2 ¼ |

high to very high |

1 or more |

| Cherries[sweet] |

18 |

1 ½-2 |

medium |

0 |

| Pear |

12 |

2 ¼-2/½ |

med. to high |

0-1/4 |

| Plum [Damson] |

14 |

2-2 ¼ |

med. to high |

0-1/4 |

| Plum [Prune] |

17 |

1 ½-2 |

med. to high |

0-1/4 |

| Peach |

10 |

2-2 ½ |

med. to high |

0-1/4 |

| Raspberries |

8 |

2 ½-3 |

high to very high |

1 or more |

| Strawberries |

5 |

2-3 ¼ |

med. To high |

0-1/2 |

| 1.) To maintain proper sugar level when the acidity is reduced by adding water, it is easier to make up a sugar solution by dissolving three pounds of sugar in enough water to fill 1-gallon jug.

2.) Addition of some acid[citric or tartaric] may help. This can be done “to taste” after the active fermentation is over. |

|

Dry table wines made from other fruits are rarely successful, but agreeable sweet wines may be made from them. The point to remember is that most fruits are lower in sugar than grapes and higher in acid. Corrections for both are almost always necessary, plus sufficient excess “Sugar to leave residual sweetness after fermentation. These fruits, with the exception of apple juice, are fermented in a crushed mass in order to obtain a maximum extraction of characteristic odors and flavors. Once fermentation is concluded, they are treated like sweet grape wine. The table will serve as a rough guide to their relative sugar content and total acidity.

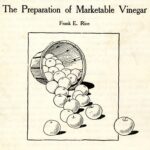

Vinegar

If a cork happens to pop out unnoticed and air reaches the wine for several weeks, there is a good chance that bacterial action will begin to convert the alcohol in the wine into acetic acid. Once the presence of acetic acid can be detected (a vinegarlike odor) the wine will lose its appeal as wine. A usable vinegar can be retrieved by encouraging the process to go to completion.

Vinegar produced from an undiluted wine will be overly strong, so an equal volume of water should be added. The container should be less than three-quarters full and closed with a loose cotton plug or covered with a piece of light cloth to keep out fruit flies.

If wine vinegar is your desired goal and no wine has started to sour, use a vinegar starter. A selected strain of vinegar starter can be purchased from some winemakers’ shops, or a wild starter may be used. Frequently the water in an air-bubbler will have a vinegar-like smell. This can be used to start a batch of vinegar. The wine is diluted with an equal volume of water and the container partly filled and covered as above.

A warm, but not hot, location will speed the process. In a month or two the vinegar should be ready. The clear portion of the vinegar can be poured or siphoned off for use. If another batch is wanted, more of the wine-water mixture can be added to the old culture.

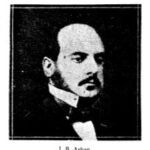

by Philip Wagner and J. R. McGrew

Home

Top of Pg.

|

Cabildo circa 1936 The Cabildo houses a rare copy of Audubon’s Bird’s of America, a book now valued at $10 million+. Should one desire to visit the Cabildo, click here to gain free entry with a lowcost New Orleans Pass. Home Top of [...] Read more →

Vishnu as the Cosmic Man (Vishvarupa) Opaque watercolour on paper – Jaipur, Rajasthan c. 1800-50 CLAIRVOYANCE AND OCCULT POWERS By Swami Panchadasi Copyright, 1916 By Advanced Thought Pub. Co. Chicago, Il INTRODUCTION. In preparing this series of lessons for students of [...] Read more →

Full Cover, rear, spine, and front Published by Piranesi Press in collaboration with Country House Essays, this beautiful paperback version of the King James Bible is now available for $79.95 at Barnes and Noble.com This is a limited Edition of 500 copies Worldwide. Click here to view other classic books [...] Read more →

Artisans world-wide spend a fortune on commercial brand oil-based gold leaf sizing. The most popular brands include Luco, Dux, and L.A. Gold Leaf. Pricing for quart size containers range from $35 to $55 depending upon retailer pricing. Fast drying sizing sets up in 2-4 hours depending upon environmental conditions, humidity [...] Read more →

The Queen Elizabeth Trust, or QEST, is an organisation dedicated to the promotion of British craftsmanship through the funding of scholarships and educational endeavours to include apprenticeships, trade schools, and traditional university classwork. The work of QEST is instrumental in keeping alive age old arts and crafts such as masonry, glassblowing, shoemaking, [...] Read more →

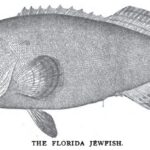

Nov. 5. 1898 Forest and Stream Pg. 371-372 The Black Grouper or Jewfish. New Smyrna, Fla., Oct. 21.—Editor Forest and Stream: It is not generally known that the fish commonly called jewfish. warsaw and black grouper are frequently caught at the New Smyrna bridge [...] Read more →

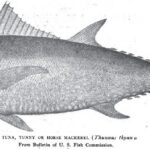

Tom Oates, aka Nabokov at en.wikipedia No two commercial tuna salads are prepared by exactly the same formula, but they do not show the wide variety characteristic of herring salad. The recipe given here is typical. It is offered, however, only as a guide. The same recipe with minor variations to suit [...] Read more →

Aw, the good old days, meet in the coffee shop with a few friends, click open the Zippo, inhale a glorious nosegay of lighter fluid, fresh roasted coffee and a Marlboro cigarette…. A Meta-analysis of Coffee Drinking, Cigarette Smoking, and the Risk of Parkinson’s Disease We conducted a [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

The following recipes form the most popular items in a nine-course dinner program: BIRD’S NEST SOUP Soak one pound bird’s nest in cold water overnight. Drain the cold water and cook in boiling water. Drain again. Do this twice. Clean the bird’s nest. Be sure [...] Read more →

Dominion, Royal St. Lawrence Yacht Club,Winner of Seawanhaka Cup, 1898. The Tail Wags the Dog. The following is a characteristic sample of those broad and liberal views on yachting which are the pride of the Boston Herald. Speaking of the coming races for the Seawanhaka international challenge cup, it says: [...] Read more →

Country House Essays has returned after a good long summer holiday. More essays soon. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

FRIED SQUIRREL & BISCUIT GRAVY 3-4 Young Squirrels, dressed and cleaned 1 tsp. Morton Salt or to taste 1 tsp. McCormick Black Pepper or to taste 1 Cup Martha White All Purpose Flour 1 Cup Hog Lard – Preferably fresh from hog killing, or barbecue table Cut up three to [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Add the following ingredients to a four or six quart crock pot, salt & pepper to taste keeping in mind that salt pork is just that, cover with water and cook on high till it boils, then cut back to low for four or five hours. A slow cooker works well, I [...] Read more →

VHF Marifoon Sailor RT144, by S.J. de Waard RADIO INFORMATION FOR BOATERS Effective 01 August, 2013, the U. S. Coast Guard terminated its radio guard of the international voice distress, safety and calling frequency 2182 kHz and the international digital selective calling (DSC) distress and safety frequency 2187.5 kHz. Additionally, [...] Read more →

” Here’s many a year to you ! Sportsmen who’ve ridden life straight. Here’s all good cheer to you ! Luck to you early and late. Here’s to the best of you ! You with the blood and the nerve. Here’s to the rest of you ! What of a weak moment’s swerve ? [...] Read more →

The element copper effectively kills viruses and bacteria. Therefore it would reason and I will assert and not only assert but lay claim to the patents for copper mesh stints to be inserted in the arteries of patients presenting with severe cases of Covid-19 with a slow release dosage of [...] Read more →

Click here to read the full text of the Hunting Act – 2004 Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Roger Scruton by Peter Helm This is one of those videos that the so-called intellectual left would rather not be seen by the general public as it makes a laughing stock of the idiots running the artworld, a multi-billion dollar business. https://archive.org/details/why-beauty-matters-roger-scruton or Click here to watch [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

New York Stock Exchange Floor September 26,1963 The Specialist as a member of a stock exchange has two functions.’ He must execute orders which other members of an exchange may leave with him when the current market price is away from the price of the orders. By executing these orders on behalf [...] Read more →

Hebborn Piranesi Before meeting with an untimely death at the hand of an unknown assassin in Rome on January 11th, 1996, master forger Eric Hebborn put down on paper a wealth of knowledge about the art of forgery. In a book published posthumously in 1997, titled The Art Forger’s Handbook, Hebborn suggests [...] Read more →

What follows is a chapter from Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward’s 1852 treatise on terrarium gardening. ON THE NATURAL CONDITIONS OF PLANTS. To enter into any lengthened detail on the all-important subject of the Natural Conditions of Plants would occupy far too much space; yet to pass it by without special notice, [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Are you considering purchasing a copper water pitcher for storing drinking water but have questions about the effects on your health? The following study may help jump-start your research. Storing Drinking-water in Copper pots Kills Contaminating Diarrhoeagenic Bacteria ABSTRACT Microbially-unsafe water is [...] Read more →

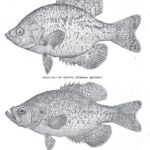

Sept. 3, 1898. Forest and Stream Pg. 188-189 How to Distinguish Fishes. BY FRED MATHER. The average angler knows by sight all the fish which he captures, but ask him to describe one and he is puzzled, and will get off on the color of the fish, which is [...] Read more →

Cleaner for Gilt Frames. Calcium hypochlorite…………..7 oz. Sodium bicarbonate……………7 oz. Sodium chloride………………. 2 oz. Distilled water…………………12 oz. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

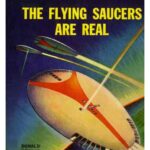

It was a strange assignment. I picked up the telegram from desk and read it a third time. NEW YORK, N.Y., MAY 9, 1949 HAVE BEEN INVESTIGATING FLYING SAUCER MYSTERY. FIRST TIP HINTED GIGANTIC HOAX TO COVER UP OFFICIAL SECRET. BELIEVE IT MAY HAVE BEEN PLANTED TO HIDE [...] Read more →

A CROCK OF SQUIRREL 4 young squirrels – quartered Salt & Pepper 1 large bunch of fresh coriander 2 large cloves of garlic 2 tbsp. salted sweet cream cow butter ¼ cup of brandy 1 tbsp. turbinado sugar 6 fresh apricots 4 strips of bacon 1 large package of Monterrey [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

A la Russie, aux ânes et aux autres – by Chagall – 1911 Marc Chagall is one of the most forged artists on the planet. Mark Rothko fakes also abound. According to available news reports, the art market is littered with forgeries of their work. Some are even thought to be [...] Read more →

Oh Glorious England, verdant fields and wandering canals… In this wonderful series of videos, the CountryHouseGent takes the viewer along as he chugs up and down the many canals crisscrossing England in his classic Narrowboat. There is nothing like a free man charting his own destiny. Read more →

Sebastian Cox is one of the UK’s premier custom furniture makers with a unique background and love for the forest. Click here to visit SebastianCox.co.uk Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Patek Phillipe hand makes the finest watches in the world. Click here to learn more. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

To Choose Poultry. When fresh, the eyes should be clear and not sunken, the feet limp and pliable, stiff dry feet being a sure indication that the bird has not been recently killed; the flesh should be firm and thick and if the bird is plucked there should be no [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Reprint from The Royal Collection Trust website: Kneller was born in Lubeck, studied with Rembrandt in Amsterdam and by 1676 was working in England as a fashionable portrait painter. He painted seven British monarchs (Charles II, James II, William III, Mary II, Anne, George I and George II), though his [...] Read more →

The Diamond Empire Home Top of [...] Read more →

Reprint from the Royal Collection Trust Website The meeting between Henry VIII and Francis I, known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold, took place between 7 to 24 June 1520 in a valley subsequently called the Val d’Or, near Guisnes to the south of Calais. The [...] Read more →

KING ARTHUR AND HIS KNIGHTS On the decline of the Roman power, about five centuries after Christ, the countries of Northern Europe were left almost destitute of a national government. Numerous chiefs, more or less powerful, held local sway, as far as each could enforce his dominion, and occasionally those [...] Read more →

Cleremont Club 44 Berkeley Square, London Home Top of Pg. Read more →

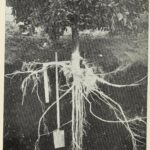

Citrus Fruit Culture THE PRINCIPAL fruit and nut trees grown commercially in the United States (except figs, tung, and filberts) are grown as varieties or clonal lines propagated on rootstocks. Almost all the rootstocks are grown from seed. The resulting seedlings then are either budded or grafted with propagating wood [...] Read more →

Jul. 30, 1898 Forest and Stream Pg. 87 Indian Mode of Hunting. I.—Beaver. Wa-sa-Kejic came over to the post early one October, and said his boy had cut his foot, and that he had no one to steer his canoe on a proposed beaver hunt. Now [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Here, where these low lush meadows lie, We wandered in the summer weather, When earth and air and arching sky, Blazed grandly, goldenly together. And oft, in that same summertime, We sought and roamed these self-same meadows, When evening brought the curfew chime, And peopled field and fold with shadows. I mind me [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Reprint from The Pitfalls of Speculation by Thomas Gibson 1906 Ed. THE PUBLIC ATTITUDE TOWARD SPECULATION THE public attitude toward speculation is generally hostile. Even those who venture frequently are prone to speak discouragingly of speculative possibilities, and to point warningly to the fact that an [...] Read more →

There is nothing more delightful than a great poetry reading to warm ones heart on a cold winter night fireside. Today is one of the coldest Valentine’s days on record, thus, nothing could be better than listening to the resonant voice of Robin Shuckbrugh, The Cotswold [...] Read more →

San Felipe Model Reprinted from FineModelShips.com with the kind permission of Dr. Michael Czytko The SAN FELIPE is one of the most favoured ships among the ship model builders. The model is elegant, very beautifully designed, and makes a decorative piece of art to be displayed at home or in the [...] Read more →

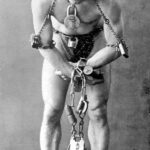

The magician delighted in exposing spiritualists as con men and frauds. By EDMUND WILSON June 24, 1925 Houdini is a short strong stocky man with small feet and a very large head. Seen from the stage, his figure, with its short legs and its pugilist’s proportions, is less impressive than at close [...] Read more →

Salmon and Sturgeon Caviar – Photo by Thor Salmon caviar was originated about 1910 by a fisherman in the Maritime Provinces of Siberia, and the preparation is a modification of the sturgeon caviar method (Cobb 1919). Salomon caviar has found a good market in the U.S.S.R. and other European countries where it [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

DECORATED or “sumptuous” furniture is not merely furniture that is expensive to buy, but that which has been elaborated with much thought, knowledge, and skill. Such furniture cannot be cheap, certainly, but the real cost of it is sometimes borne by the artist who produces rather than by the man who may [...] Read more →

Gary Kravit is an airline pilot and artist. He also owns and operates https://theultimatetaboret.com. You may view Gary’s art at https://garrykravitart.blogspot.com/ Home Top of Pg. Read more →

King Leopold Butcher of the Congo For the somewhat startling suggestion in the heading of this interview, the missionary interviewed is in no way responsible. The credit of it, or, if you like, the discredit, belongs entirely to the editor of the Review, who, without dogmatism, wishes to pose the question as [...] Read more →

The Hunt Saboteur is a national disgrace barking out loud, black mask on her face get those dogs off, get them off she did yell until a swift kick from me mare her voice it did quell and sent the Hunt Saboteur scurrying up vale to the full cry of hounds drowning out her [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Wine Making Grapes are the world’s leading fruit crop and the eighth most important food crop in the world, exceeded only by the principal cereals and starchytubers. Though substantial quantities are used for fresh fruit, raisins, juice and preserves, most of the world’s annual production of about 60 million [...] Read more →

Early Texas photo of Tarpon catch – Not necessarily the one mentioned below… July 2, 1898. Forest and Stream Pg.10 Texas Tarpon. Tarpon, Texas.—Mr. W. B. Leach, of Palestine, Texas, caught at Aransas Pass Islet, on June 14, the largest tarpon on record here taken with rod and reel. The [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

From Allen’s Indian Mail, December 3rd, 1851 BOMBAY. MUSULMAN FANATICISM. On the evening of November 15th, the little village of Mahim was the scene of a murder, perhaps the most determined which has ever stained the annals of Bombay. Three men were massacred in cold blood, in a house used [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Banana Propagation Reprinted from the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA.org) The traditional means of obtaining banana planting material (“seed”) is to acquire suckers from one’s own banana garden, from a neighbor, or from a more distant source. This method served to spread common varieties around the world and to multiply them [...] Read more →

The Clermont Club Reprint from London Bisnow/UK At £23M, its sale is not the biggest property deal in the world. But the Clermont Club casino in Berkeley Square in London could lay claim to being the most significant address in modern finance — it is where the concept of what is today [...] Read more →

William Wyggeston’s chantry house, built around 1511, in Leicester: The building housed two priests, who served at a chantry chapel in the nearby St Mary de Castro church. It was sold as a private dwelling after the dissolution of the chantries. A Privately Built Chapel Chantry, chapel, generally within [...] Read more →

It is unnecessary to point out that low-grade fruit may often be used to advantage in the preparation of vinegar. This has always been true in the case of apples and may be true with other fruit, especially grapes. The use of grapes for wine making is an outlet which [...] Read more →

Mortlake Tapestries at Chatsworth House Click here to read copy of Daemonologie Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Charles Dickens wrote much more than novels. In fact he turned out several very interesting dictionaries to include one of London, one of Paris and one on London’s long meandering river Thames. Click here to read a copy of the Dictionary of the Thames. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

. Home Top of [...] Read more →

Dutch artist Herman de Vries – Photo taken by son Vince The two videos below of Herman de Vries at work at the Venice Bienalle 2015 are quite inspiring. So inspiring in fact that I moved into a cave for two weeks and wrote Shakespearean tragedy with charcoal. Filled with great joy [...] Read more →

A rhetorical question? Genuine concern? In this essay we are examining another form of matter otherwise known as national literary matters, the three most important of which being the Matter of Rome, Matter of France, and the Matter of England. Our focus shall be on the Matter of England or [...] Read more →

THE FOWLING PIECE, from the Shooter’s Guide by B. Thomas – 1811. I AM perfectly aware that a large volume might be written on this subject; but, as my intention is to give only such information and instruction as is necessary for the sportsman, I shall forbear introducing any extraneous [...] Read more →

Click here to access the world’s most powerful Import/Export Research Database on the Planet. With this search engine one is able to access U.S. Customs and other government data showing suppliers for any type of company in the United States. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

As reported in the The Colac Herald on Friday July 17, 1903 Pg. 8 under Art Appreciation as a reprint from the Westminster Gazette ART APPRECIATION IN THE COMMONS. The appreciation of art as well as of history which is entertained by the average member of the [...] Read more →

Photo by Greg O’Beirne Home Top of Pg. Read more →

THE answer to the question, What is fortune has never been, and probably never will be, satisfactorily made. What may be a fortune for one bears but small proportion to the colossal possessions of another. The scores or hundreds of thousands admired and envied as a fortune in most of our communities [...] Read more →

The Ardabil Carpet – Made in the town of Ardabil in north-west Iran, the burial place of Shaykh Safi al-Din Ardabili, who died in 1334. The Shaykh was a Sufi leader, ancestor of Shah Ismail, founder of the Safavid dynasty (1501-1722). While the exact origins of the carpet are unclear, it’s believed to have [...] Read more →

THE sense of a consecutive tradition has so completely faded out of English art that it has become difficult to realise the meaning of tradition, or the possibility of its ever again reviving; and this state of things is not improved by the fact that it is due to uncertainty of purpose, [...] Read more →

Note on Watercolour: F.A. Molony (fl. 1930-1938) was a Major in the Royal Engineers. The National Army Museum hold his work. His work was also shown at an exhibition of officers work at the R.B.A. Galleries (Army Officers’ Art Society) Description from Youtube: June 2015 will see [...] Read more →

Absolutely Brilliant! And as I am quite certain you will become a fan, there’s more! Home Top of Pg. Read more →

From Dr. Marvel’s 1929 book entitled Hoodoo for the Common Man, we find his infamous Hoochie Coochie Hex. What follows is a verbatim transcription of the text: The Hoochie Coochie Hex should not be used in conjunction with any other Hexes. This can lead to [...] Read more →

Toxicity of Rhododendron From Countrysideinfo.co.UK “Potentially toxic chemicals, particularly ‘free’ phenols, and diterpenes, occur in significant quantities in the tissues of plants of Rhododendron species. Diterpenes, known as grayanotoxins, occur in the leaves, flowers and nectar of Rhododendrons. These differ from species to species. Not all species produce them, although Rhododendron ponticum [...] Read more →

A General Process for Making Wine. Gathering the Fruit Picking the Fruit Bruising the Fruit Vatting the Fruit Vinous Fermentation Drawing the Must Pressing the Must Casking the Must Spirituous Fermentation Racking the Wine Bottling and Corking the Wine Drinking the Wine GATHERING THE FRUIT. It is of considerable consequence [...] Read more →

Photo Caption: The Marquis of Zetland, KC, PC – otherwise known as Lawrence Dundas Son of: John Charles Dundas and: Margaret Matilda Talbot born: Friday 16 August 1844 died: Monday 11 March 1929 at Aske Hall Occupation: M.P. for Richmond Viceroy of Ireland Vice Lord Lieutenant of North Yorkshire Lord – in – Waiting [...] Read more →

H. M. Scarth, Rector of Wrington By the death of Mr. Scarth on the 5th of April, at Tangier, where he had gone for his health’s sake, the familiar form of an old and much valued Member of the Institute has passed away. Harry Mengden Scarth was bron at Staindrop in Durham, [...] Read more →

Click here to read the Condon Report Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Sucker The components of any given market place include both physical structures set up to accommodate trading, and participants to include buyers, sellers, brokers, agents, barkers, pushers, auctioneers, agencies, and propaganda outlets, and banking or transaction exchange facilities. Markets are generally set up by sellers as it is in their [...] Read more →

CLAIRVOYANCE by C. W. Leadbeater Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Pub. House [1899] CHAPTER IX – METHODS OF DEVELOPMENT When a men becomes convinced of the reality of the valuable power of clairvoyance, his first question usually is, “How can [...] Read more →

Gilbert Stewart – Sir Joshua Reynolds SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS‘ WORKING COLOURS, WITH THE ORDER IN WHICH THEY WERE ARRANGED ON HIS PALLETTE. “For painting the flesh, black, blue black, white, lake, carmine, orpiment, yellow ochre, ultramarine, and varnish. “To lay the [...] Read more →

H.F. Leonard was an instructor in wrestling at the New York Athletic Club. Katsukum Higashi was an instructor in Jujitsu. “I say with emphasis and without qualification that I have been unable to find anything in jujitsu which is not known to Western wrestling. So far as I can see, [...] Read more →

The Chicago portion of the The Great Train Story at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. by Interiority Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Dried Norwegian Salt Cod Fried fish cakes are sold rather widely in delicatessens and at prepared food counters of department stores in the Atlantic coastal area. This product has possibilities for other sections of the country. Ingredients: Home Top of [...] Read more →

EBAY’S FRAUD PROBLEM IS GETTING WORSE EBay has had a problem with fraudulent sellers since its inception back in 1995. Some aspects of the platform have improved with algorithms and automation, but others such as customer service and fraud have gotten worse. Small sellers have definitely been hurt by eBay’s [...] Read more →

King George IV was known far and wide as the dandy king, incompetent, ugly, and vulgar. As Prince regent, prior to his assent to the throne, he kept fast company with Beau Brummel, King of Dandies, a man sixteen years his younger. And decadence followed. King George was a gambler, philanderer, and [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

John Atkinson Grimshaw – Glasgow Saturday Night Home Top of Pg. Read more →

*note – Billesdon and Billesden have both been used to name the hunt. BILLESDEN COPLOW POEM [From “Reminiscences of the late Thomas Assheton Smith, Esq”] The run celebrated in the following verses took place on the 24th of February, 1800, when Mr. Meynell hunted Leicestershire, and has since been [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

How happy is he born and taught. That serveth not another’s will; Whose armour is his honest thought, And simple truth his utmost skill Whose passions not his masters are; Whose soul is still prepared for death, Untied unto the world by care Of public fame or private breath; Who envies none that chance [...] Read more →

Looking to spice up your dinner? Let’s hop along and cook some roo. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Click here to learn more about The Tallis Scholars Home Top of Pg. Read more →

“Saint John’s Gate, Clerkenwell, the main gateway to the Priory of Saint John of Jerusalem,” black and white photograph by the British photographer Henry Dixon, 1880. The church was founded in the 12th century by Jordan de Briset, a Norman knight. Prior Docwra completed the gatehouse shown in this photograph in 1504. The gateway [...] Read more →

Jan Verkolje Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was the first person to describe gout or uric acid crystals 1679. For one suffering gout, the following vitamins, herbs, and extracts may be worth looking into: Vitamin C Folic Acid – Folic Acid is a B vitamin and is also known as B9 – [Known food [...] Read more →

Paul Thorpe, Brighton, U.K. The YouTube watch collecting world is rather tight-knit and small, but growing, as watches became a highly coveted commodity during the recent world-wide pandemic and fueled an explosion of online watch channels. There is one name many know, The Time Piece Gentleman. This name for me [...] Read more →

Edwin Austin Abbey. King Lear, Act I, Scene I (Cordelia’s Farewell) The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Dates: 1897-1898 Dimensions: Height: 137.8 cm (54.25 in.), Width: 323.2 cm (127.24 in.) Medium: Painting – oil on canvas Home Top of Pg. Read more →

PEACH BRANDY 2 gallons + 3 quarts boiled water 3 qts. peaches, extremely ripe 3 lemons, cut into sections 2 sm. pkgs. yeast 10 lbs. sugar 4 lbs. dark raisins Place peaches, lemons and sugar in crock. Dissolve yeast in water (must NOT be to hot). Stir thoroughly. Stir daily for 7 days. Keep [...] Read more →

Roger Scruton – Why Beauty Matters (2009) from Mirza Akdeniz on Vimeo. Click here for another site on which to view this video. Sadly, Sir Roger Scruton passed away a few days ago—January 12th, 2020. Heaven has gained a great philosopher. Home Top of [...] Read more →

Over the years I have observed a decline in manners amongst young men as a general principle and though there is not one particular thing that may be asserted as the causal reason for this, one might speculate… Self-awareness and being aware of one’s surroundings in social interactions [...] Read more →

First Pineapple Grown in England Click here to read an excellent article on the history of pineapple growing in the UK. Should one be interested in serious mass scale production, click here for scientific resources. Growing pineapples in the UK. The video below demonstrates how to grow pineapples in Florida. [...] Read more →

Royal Exchange and The Bank of England From How to Make Money; and How to Keep it, Or, Capital and Labor based on the works of Thomas A. Davies Revised & Rewritten with Additions by Henry A. Ford A.M. – 1884 CHAPTER XXVI BANKING AND INSURANCE. I [...] Read more →

This massive volume gives one a real visual sense of what it was like running a highly efficient colonial operation in the early 20rh Century. It will also go a long way to help anyone wishing to understand modern political intrigue in the Middle-East. Click here to read A Survey of Palestine [...] Read more →

Twinings London – photo by Elisa.rolle Is the tea in your cup genuine? The fact is, had one been living in the early 19th Century, one might occasionally encounter a counterfeit cup of tea. Food adulterations to include added poisonings and suspect substitutions were a common problem in Europe at [...] Read more →

July, 16, l898 Forest and Stream Pg. 48 Tuna and Tarpon. New York, July 1.—Editor Forest and Stream: If any angler still denies the justice of my claim, as made in my article in your issue of July 2, that “the tuna is the grandest game [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Resolution adapted at the New Orleans Convention of the American Institute of Banking, October 9, 1919: “Ours is an educational association organized for the benefit of the banking fraternity of the country and within our membership may be found on an equal basis both employees and employers; [...] Read more →

Jujitsu training 1920 in Japanese agricultural school. CHAPTER V THE VALUE OF EVEN TEMPER IN ATHLETICS—SOME OF THE FEATS THAT REQUIRE GOOD NATURE In the writer’s opinion it becomes necessary to make at this point some suggestions relative to a very important part of the training in jiu-jitsu. [...] Read more →

Officers and men of the 13th Light Dragoons, British Army, Crimea. Rostrum photograph of photographer’s original print, uncropped and without color correction. Survivors of the Charge. Half a league, half a league, Half a league onward, All in the valley of Death Rode the six hundred. “Forward, the Light Brigade! Charge for the [...] Read more →

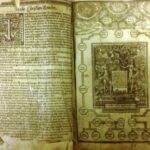

Richard Barker KJ Title Pg. Robert Barker was the printer of the first edition of the King James Bible in 1611. He was the printer to King James I and son of Christopher Barker, printer to Queen Victoria I. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

ORIGIN OF THE APOTHECARY. The origin of the apothecary in England dates much further back than one would suppose from what your correspondent, “A Barrister-at-Law,” says about it. It is true he speaks only of apothecaries as a distinct branch of the medical profession, but long before Henry VIII’s time [...] Read more →

Reprint from The Sportsman’s Cabinet and Town and Country Magazine, Vol I. Dec. 1832, Pg. 94-95 To the Editor of the Cabinet. SIR, Possessing that anxious feeling so common among shooters on the near approach of the 12th of August, I honestly confess I was not able [...] Read more →

AB Bookman’s 1948 Guide to Describing Conditions: As New is self-explanatory. It means that the book is in the state that it should have been in when it left the publisher. This is the equivalent of Mint condition in numismatics. Fine (F or FN) is As New but allowing for the normal effects of [...] Read more →

Furniture Polishing Cream. Animal oil soap…………………….1 onuce Solution of potassium hydroxide…. .5 ounces Beeswax……………………………1 pound Oil of turpentine…………………..3 pints Water, enough to make……………..5 pints Dissolve the soap in the lye with the aid of heat; add this solution all at once to the warm solution of the wax in the oil. Beat [...] Read more →

BLACKBERRY WINE 5 gallons of blackberries 5 pound bag of sugar Fill a pair of empty five gallon buckets half way with hot soapy water and a ¼ cup of vinegar. Wash thoroughly and rinse. Fill one bucket with two and one half gallons of blackberries and crush with [...] Read more →

A Lecture Delivered at the Guildhall, March 2, 1853 by Rev. H.M. Scarth, M.A., Rector of Bathwick. To understand the ancient history of the country in which we live, to know something of the arts and manners of the people who have preceded us, to ascertain what we owe [...] Read more →

Country House Christmas Pudding Ingredients 1 cup Christian Bros Brandy ½ cup Myer’s Dark Rum ½ cup Jim Beam Whiskey 1 cup currants 1 cup sultana raisins 1 cup pitted prunes finely chopped 1 med. apple peeled and grated ½ cup chopped dried apricots ½ cup candied orange peel finely chopped 1 ¼ cup [...] Read more →

Wojna Kalmarska – 1611 The Kalmar War From The Historian’s History of the World (In 25 Volumes) by Henry Smith William L.L.D. – Vol. XVI.(Scandinavia) Pg. 308-310 The northern part of the Scandinavian peninsula, as already noticed, had been peopled from the remotest times by nomadic tribes called Finns or Cwenas by [...] Read more →

WITCHCRAFT, SORCERY, MAGIC AND OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL PHENOMENA AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS ON MILITARY AND PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS IN THE CONGO This report has been prepared in response to a query posed by ODCS/OPS, Department of the Army, regarding the purported use of witchcraft, sorcery, and magic by insurgent elements in the Republic [...] Read more →

Silverfish damage to book – photo by Micha L. Rieser The beauty of hunting silverfish is that they are not the most clever of creatures in the insect kingdom. Simply take a small clean glass jar and wrap it in masking tape. The masking tape gives the silverfish something to [...] Read more →

What is follows is an historical article that appeared in The Hartford Courant in 1916 about the arsenic murders carried out by Mrs. Archer-Gilligan. This story is the basis for the 1944 Hollywood film “Arsenic and Old Lace” starring Cary Grant and Priscilla Lane and directed by Frank Capra. The [...] Read more →

To learn more about Julian McDonnell, film director, click here. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

To Clean Watch Chains. Gold or silver watch chains can be cleaned with a very excellent result, no matter whether they may be matt or polished, by laying them for a few seconds in pure aqua ammonia; they are then rinsed in alcohol, and finally. shaken in clean sawdust, free from sand. [...] Read more →

Welcome to Country House Essays. Enjoy. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

U.S. SENATE PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS STAFF REPORT ON DIVIDEND TAX ABUSE: HOW OFFSHORE ENTITIES DODGE TAXES ON U.S. STOCK DIVIDENDS September 11, 2008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Each year, the United States loses an estimated [...] Read more →

Hudson Bay: Trappers, 1892. N’Talking Musquash.’ Fur Trappers Of The Hudson’S Bay Company Talking By A Fire. Engraving After A Drawing By Frederic Remington, 1892. Indian Modes of Hunting. IV.—Musquash. In Canada and the United States, the killing of the little animal known under the several names of [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

TROF. C. F. HOLDFER AND HIS 183LBS. TUNA, WITH BOATMAN JIM GARDNER. July 2, 1898. Forest and Stream Pg. 11 The Tuna Record. Avalon. Santa Catalina Island. Southern California, June 16.—Editor Forest and Stream: Several years ago the writer in articles on the “Game Fishes of the Pacific Slope,” in [...] Read more →

Stoke Park Pavillions Stoke Park Pavilions, UK, view from A405 Road. photo by Wikipedia user Cj1340 From Wikipedia: Stoke Park – the original house Stoke park was the first English country house to display a Palladian plan: a central house with balancing pavilions linked by colonnades or [...] Read more →

From The How and When, An Authoritative reference reference guide to the origin, use and classification of the world’s choicest vintages and spirits by Hyman Gale and Gerald F. Marco. The Marco name is of a Chicago family that were involved in all aspects of the liquor business and ran Marco’s Bar [...] Read more →

Testing the Irish Blue Terrier Breed in 1923. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Click here to visit Ovation Guitars Ovation Patent Drawing 1975 Click here to read a copy of the 1975 Patent for the Ovation Guitar Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Chipping a Turpentine Tree DISTILLING TURPENTINE One of the Most Important Industries of the State of Georgia Injuring the Magnificent Trees Spirits, Resin, Tar, Pitch, and Crude Turpentine all from the Long Leaved Pine – “Naval Stores” So Called. Dublin, Ga., May 8. – One of the most important industries [...] Read more →

Biograph Theater, where John Dillinger was gunned down by the FBI on July 22, 1934 The Great Depression was on—highway based crime was rampant, the gangsters dressed as well as the bankers they robbed, and and Henry Ford’s big beautiful V8 sedan was the getaway car of choice for both wheelman and [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Oct. 22, 1898 Forest and Stream Pg. 324 An Alaskan Moose Head. Tacoma, Washington; Oct. 1.—Editor Forest and Stream: In your issue of March 6, 1897, you showed cut of a pair of moose horns belonging to me that spread 73 1/2 in.— at that time [...] Read more →

Saint Francis of Assisi, founder of the mendicant Order of Friars Minor, as painted by El Greco. Catholic religious order Catholic religious orders are one of two types of religious institutes (‘Religious Institutes’, cf. canons 573–746), the major form of consecrated life in the Roman Catholic Church. They are organizations of laity [...] Read more →

|

The magician delighted in exposing spiritualists as con men and frauds. By EDMUND WILSON June 24, 1925 Houdini is a short strong stocky man with small feet and a very large head. Seen from the stage, his figure, with its short legs and its pugilist’s proportions, is less impressive than at close [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of [...] Read more →

Robert W. Service (b.1874, d.1958) There are strange things done in the midnight sun By the men who moil for gold; The Arctic trails have their secret tales That would make your blood run cold; The Northern Lights have seen queer sights, But the queerest they ever did see Was that night [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

July 2, 1898 Forest and Stream, Fresh-Water Angling. No. IX.—The Two Crappies. BY FRED MATHER. Fishing In Tree Tops. Here a short rod, say 8ft., is long enough, and the line should not be much longer than the rod. A reel is not [...] Read more →

King Leopold Butcher of the Congo For the somewhat startling suggestion in the heading of this interview, the missionary interviewed is in no way responsible. The credit of it, or, if you like, the discredit, belongs entirely to the editor of the Review, who, without dogmatism, wishes to pose the question as [...] Read more →

Absolutely Brilliant! And as I am quite certain you will become a fan, there’s more! Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

http://www.vermeerscamera.co.uk/home.htm Home Top of Pg. Read more →

The Apex Building, headquarters of the Federal Trade Commission, on Constitution Avenue and 7th Streets in Washington, D.C.. The building was designed by Edward H. Bennett under the purview of Secretary of the Treasury Andrew W. Mellon, and was completed in 1938 at a cost of $125 million. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Testing the Irish Blue Terrier Breed in 1923. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Book Conservators, Mitchell Building, State Library of New South Wales, 29.10.1943, Pix Magazine The following is taken verbatim from a document that appeared several years ago in the Maine State Archives. It seems to have been removed from their website. I happened to have made a physical copy of it at the [...] Read more →

*note – Billesdon and Billesden have both been used to name the hunt. BILLESDEN COPLOW POEM [From “Reminiscences of the late Thomas Assheton Smith, Esq”] The run celebrated in the following verses took place on the 24th of February, 1800, when Mr. Meynell hunted Leicestershire, and has since been [...] Read more →

NEWSPAPER.-Printed sheets published at stated intervals, chiefly for the purpose of conveying intelligence on current events. The Romans wrote out an account of the most memorable occurrences of the day, which were sent to public officials. They were entitled Acta Durna, and read substantially like the local column of a [...] Read more →

The following recipes form the most popular items in a nine-course dinner program: BIRD’S NEST SOUP Soak one pound bird’s nest in cold water overnight. Drain the cold water and cook in boiling water. Drain again. Do this twice. Clean the bird’s nest. Be sure [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

TROF. C. F. HOLDFER AND HIS 183LBS. TUNA, WITH BOATMAN JIM GARDNER. July 2, 1898. Forest and Stream Pg. 11 The Tuna Record. Avalon. Santa Catalina Island. Southern California, June 16.—Editor Forest and Stream: Several years ago the writer in articles on the “Game Fishes of the Pacific Slope,” in [...] Read more →

From Allen’s Indian Mail, December 3rd, 1851 BOMBAY. MUSULMAN FANATICISM. On the evening of November 15th, the little village of Mahim was the scene of a murder, perhaps the most determined which has ever stained the annals of Bombay. Three men were massacred in cold blood, in a house used [...] Read more →

H. M. Scarth, Rector of Wrington By the death of Mr. Scarth on the 5th of April, at Tangier, where he had gone for his health’s sake, the familiar form of an old and much valued Member of the Institute has passed away. Harry Mengden Scarth was bron at Staindrop in Durham, [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Photo by Greg O’Beirne Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Dried Norwegian Salt Cod Fried fish cakes are sold rather widely in delicatessens and at prepared food counters of department stores in the Atlantic coastal area. This product has possibilities for other sections of the country. Ingredients: Home Top of [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Reprint from The Sportsman’s Cabinet and Town and Country Magazine, Vol I. Dec. 1832, Pg. 94-95 To the Editor of the Cabinet. SIR, Possessing that anxious feeling so common among shooters on the near approach of the 12th of August, I honestly confess I was not able [...] Read more →

Toxicity of Rhododendron From Countrysideinfo.co.UK “Potentially toxic chemicals, particularly ‘free’ phenols, and diterpenes, occur in significant quantities in the tissues of plants of Rhododendron species. Diterpenes, known as grayanotoxins, occur in the leaves, flowers and nectar of Rhododendrons. These differ from species to species. Not all species produce them, although Rhododendron ponticum [...] Read more →

From Conquest of the Tropics by Frederick Upham Adams Chapter VI – Birth of the United Fruit Company Only those who have lived in the tropic and are familiar with the hazards which confront the cultivation and marketing of its fruits can readily understand [...] Read more →

Vishnu as the Cosmic Man (Vishvarupa) Opaque watercolour on paper – Jaipur, Rajasthan c. 1800-50 CLAIRVOYANCE AND OCCULT POWERS By Swami Panchadasi Copyright, 1916 By Advanced Thought Pub. Co. Chicago, Il INTRODUCTION. In preparing this series of lessons for students of [...] Read more →

A rhetorical question? Genuine concern? In this essay we are examining another form of matter otherwise known as national literary matters, the three most important of which being the Matter of Rome, Matter of France, and the Matter of England. Our focus shall be on the Matter of England or [...] Read more →

Hebborn Piranesi Before meeting with an untimely death at the hand of an unknown assassin in Rome on January 11th, 1996, master forger Eric Hebborn put down on paper a wealth of knowledge about the art of forgery. In a book published posthumously in 1997, titled The Art Forger’s Handbook, Hebborn suggests [...] Read more →

Click here to read The First Greek Book by John Williams White The First Greek Book - 15.7MB IN MEMORIAM JOHN WILLIAMS WHITE The death, on May 9, of John Williams White, professor of Greek in Harvard University, touches a large number of classical [...] Read more →

Tom Oates, aka Nabokov at en.wikipedia No two commercial tuna salads are prepared by exactly the same formula, but they do not show the wide variety characteristic of herring salad. The recipe given here is typical. It is offered, however, only as a guide. The same recipe with minor variations to suit [...] Read more →

THE sense of a consecutive tradition has so completely faded out of English art that it has become difficult to realise the meaning of tradition, or the possibility of its ever again reviving; and this state of things is not improved by the fact that it is due to uncertainty of purpose, [...] Read more →

Click here to view a copy of Arban’s Complete Conservatory Method for Cornet Click on the blue button to download a free copy of Arban’s Complete Conservatory Method for Cornet Arban's - 11.8MB For trumpet players wishing to practice daily using an iPad, simply click [...] Read more →

The Chicago portion of the The Great Train Story at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. by Interiority Home Top of Pg. Read more →

“The Leda, in the Colonna palace, by Correggio, is dead-coloured white and black, with ultramarine in the shadow ; and over that is scumbled, thinly and smooth, a warmer tint,—I believe caput mortuum. The lights are mellow ; the shadows blueish, but mellow. The picture is painted on panel, in [...] Read more →

Fed Chariman William McChesney Martin – 1952-1970 [Editor note: This response in my mind is quite hilarious…and to the point…who the heck would want to give up 6% interest year after year after year after year? ] You HAVE ASKED that I appear before you today in connection with your consideration [...] Read more →

Add 3 quarts clover blossoms* to 4 quarts of boiling water removed from heat at point of boil. Let stand for three days. At the end of the third day, drain the juice into another container leaving the blossoms. Add three quarts of fresh water and the peel of one lemon to the blossoms [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Add the following ingredients to a four or six quart crock pot, salt & pepper to taste keeping in mind that salt pork is just that, cover with water and cook on high till it boils, then cut back to low for four or five hours. A slow cooker works well, I [...] Read more →

Liquorice, the roots of Glycirrhiza Glabra, a perennial plant, a native of the south of Europe, but cultivated to some extent in England, particularly at Mitcham, in Surrey. Its root, which is its only valuable part, is long, fibrous, of a yellow colour, and when fresh, very juicy. [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Felix Weihs de Weldon, age 96, died broke in the year 2003 after successive bankruptcies and accumulating $4 million dollars worth of debt. Most of the debt was related to the high cost of love for a wife living with Alzheimer’s. Health care costs to maintain his first wife, Margot, ran $500 per [...] Read more →

Oct. 22, 1898 Forest and Stream Pg. 324 An Alaskan Moose Head. Tacoma, Washington; Oct. 1.—Editor Forest and Stream: In your issue of March 6, 1897, you showed cut of a pair of moose horns belonging to me that spread 73 1/2 in.— at that time [...] Read more →

Hudson Bay: Trappers, 1892. N’Talking Musquash.’ Fur Trappers Of The Hudson’S Bay Company Talking By A Fire. Engraving After A Drawing By Frederic Remington, 1892. Indian Modes of Hunting. IV.—Musquash. In Canada and the United States, the killing of the little animal known under the several names of [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

KING ARTHUR AND HIS KNIGHTS On the decline of the Roman power, about five centuries after Christ, the countries of Northern Europe were left almost destitute of a national government. Numerous chiefs, more or less powerful, held local sway, as far as each could enforce his dominion, and occasionally those [...] Read more →

WITCHCRAFT, SORCERY, MAGIC AND OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL PHENOMENA AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS ON MILITARY AND PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS IN THE CONGO This report has been prepared in response to a query posed by ODCS/OPS, Department of the Army, regarding the purported use of witchcraft, sorcery, and magic by insurgent elements in the Republic [...] Read more →

Cleaner for Gilt Frames. Calcium hypochlorite…………..7 oz. Sodium bicarbonate……………7 oz. Sodium chloride………………. 2 oz. Distilled water…………………12 oz. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Noel Desenfans and Sir Francis Bourgeois, circa 1805 by Paul Sandby, watercolour on paper The Dulwich Picture Gallery was England’s first purpose-built art gallery and considered by some to be England’s first national gallery. Founded by the bequest of Sir Peter Francis Bourgois, dandy, the gallery was built to display his vast [...] Read more →

Photo by Rebecca Humann Texas Tea Recipe 2 oz Cuervo Gold Tequila Home Top of [...] Read more →

Click here to access the world’s most powerful Import/Export Research Database on the Planet. With this search engine one is able to access U.S. Customs and other government data showing suppliers for any type of company in the United States. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

What is follows is an historical article that appeared in The Hartford Courant in 1916 about the arsenic murders carried out by Mrs. Archer-Gilligan. This story is the basis for the 1944 Hollywood film “Arsenic and Old Lace” starring Cary Grant and Priscilla Lane and directed by Frank Capra. The [...] Read more →

AB Bookman’s 1948 Guide to Describing Conditions: As New is self-explanatory. It means that the book is in the state that it should have been in when it left the publisher. This is the equivalent of Mint condition in numismatics. Fine (F or FN) is As New but allowing for the normal effects of [...] Read more →

To learn more about Julian McDonnell, film director, click here. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

It is a pity that the traditions and literature in praise of fly fishing have unconsciously hampered instead of expanded this graceful, effective sport. Many a sportsman has been anxious to share its joys, but appalled by the rapture of expression in describing its countless thrills and niceties he has been literally [...] Read more →

Click here to view more great Italian recipes. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

INTRODUCTION The idea of compiling this little volume occurred to me while on a visit to some friends at their summer home in a quaint New England village. The little town had once been a thriving seaport, but now consisted of hardly more than a dozen old-fashioned Colonial houses facing [...] Read more →

U.S. SENATE PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS STAFF REPORT ON DIVIDEND TAX ABUSE: HOW OFFSHORE ENTITIES DODGE TAXES ON U.S. STOCK DIVIDENDS September 11, 2008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Each year, the United States loses an estimated [...] Read more →

Welcome to Country House Essays. Enjoy. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Roger Scruton by Peter Helm This is one of those videos that the so-called intellectual left would rather not be seen by the general public as it makes a laughing stock of the idiots running the artworld, a multi-billion dollar business. https://archive.org/details/why-beauty-matters-roger-scruton or Click here to watch [...] Read more →

Cannone nel castello di Haut-Koenigsbourg, photo by Gita Colmar Without any preliminary cleaning the bronze object to be treated is hung as cathode into the 2 per cent. caustic soda solution and a low amperage direct current is applied. The object is suspended with soft copper wires and is completely immersed into [...] Read more →

THE FOWLING PIECE, from the Shooter’s Guide by B. Thomas – 1811. I AM perfectly aware that a large volume might be written on this subject; but, as my intention is to give only such information and instruction as is necessary for the sportsman, I shall forbear introducing any extraneous [...] Read more →

Foie gras with Sauternes, Photo by Laurent Espitallier As an Appetizer Pale dry Sherry, with or without bitters, chilled or not. Plain or mixed Vermouth, with or without bitters. A dry cocktail. With Oysters, Clams or Caviar A dry flinty wine such as Chablis, Moselle, Champagne. Home Top of [...] Read more →

July 9, 1898. Forest and Stream Pg. 25 Some Notes on American Ship-Worms. [Read before the American Fishes Congress at Tampa.] While we wish to preserve and protect most of the products of our waters, these creatures we would gladly obliterate from the realm of living things. For [...] Read more →

Home Top of [...] Read more →

The rigging of an old square rig in London, United Kingdom. Photograph taken by Melongrower. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Click here to learn more about The Tallis Scholars Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

THE ABC OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM WH Y THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM WAS CALLED INTO BEING, THE MAIN FEATURES OF ITS ORGANIZATION , AND HOW IT WORKS B Y EDWIN WALTER KEMMERER, PH.D. PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS AND FINANCE IN PRINCETON UNIVERSITY AND MEMBER OF [...] Read more →

It is unnecessary to point out that low-grade fruit may often be used to advantage in the preparation of vinegar. This has always been true in the case of apples and may be true with other fruit, especially grapes. The use of grapes for wine making is an outlet which [...] Read more →

Crewe Hall Dining Room THE transient tenure that most of us have in our dwellings, and the absorbing nature of the struggle that most of us have to make to win the necessary provisions of life, prevent our encouraging the manufacture of well-wrought furniture. We mean to outgrow [...] Read more →

First Pineapple Grown in England Click here to read an excellent article on the history of pineapple growing in the UK. Should one be interested in serious mass scale production, click here for scientific resources. Growing pineapples in the UK. The video below demonstrates how to grow pineapples in Florida. [...] Read more →

A General Process for Making Wine. Gathering the Fruit Picking the Fruit Bruising the Fruit Vatting the Fruit Vinous Fermentation Drawing the Must Pressing the Must Casking the Must Spirituous Fermentation Racking the Wine Bottling and Corking the Wine Drinking the Wine GATHERING THE FRUIT. It is of considerable consequence [...] Read more →

EBAY’S FRAUD PROBLEM IS GETTING WORSE EBay has had a problem with fraudulent sellers since its inception back in 1995. Some aspects of the platform have improved with algorithms and automation, but others such as customer service and fraud have gotten worse. Small sellers have definitely been hurt by eBay’s [...] Read more →

King Arthur, Legends, Myths & Maidens is a massive book of Arthurian legends. This limited edition paperback was just released on Barnes and Noble at a price of $139.00. Although is may seem a bit on the high side, it may prove to be well worth its price as there are only [...] Read more →

The first published illustration of Nicotiana tabacum by Pena and De L’Obel, 1570–1571 (shrpium adversana nova: London). Tobacco can be used for medicinal purposes, however, the ongoing American war on smoking has all but obscured this important aspect of ancient plant. Tobacco is considered to be an indigenous plant of [...] Read more →

The following research discussion is from a study funded by the U.S. National Institute of Health entitled: Boschniakia rossica prevents the carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in rat. It may be of interest to heavy drinkers. Home Top of [...] Read more →

Today I shall share a bit of market wisdom that will be hard to swallow for some Rolex owners, especially if they bought their Submariner at the top of the magical Covid Watch Bubble that has now collapsed. History often repeats itself, even in the stock market, but when [...] Read more →

Officers and men of the 13th Light Dragoons, British Army, Crimea. Rostrum photograph of photographer’s original print, uncropped and without color correction. Survivors of the Charge. Half a league, half a league, Half a league onward, All in the valley of Death Rode the six hundred. “Forward, the Light Brigade! Charge for the [...] Read more →

. Home Top of [...] Read more →

? This video by AT Restoration is the best hands on video I have run across on the basics of classic upholstery. Watch a master at work. Simply amazing. Tools: Round needles: https://amzn.to/2S9IhrP Double pointed hand needle: https://amzn.to/3bDmWPp Hand tools: https://amzn.to/2Rytirc Staple gun (for beginner): https://amzn.to/2JZs3x1 Compressor [...] Read more →

Fred Kummerow on statin drugs (excerpt) from Jeremy Stuart on Vimeo. Dr. Kummerow passed away at the ripe old age of 102 in 2017. Click here to visit Dr. Mercola’s website. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

As reported in the The Colac Herald on Friday July 17, 1903 Pg. 8 under Art Appreciation as a reprint from the Westminster Gazette ART APPRECIATION IN THE COMMONS. The appreciation of art as well as of history which is entertained by the average member of the [...] Read more →

Oh Glorious England, verdant fields and wandering canals… In this wonderful series of videos, the CountryHouseGent takes the viewer along as he chugs up and down the many canals crisscrossing England in his classic Narrowboat. There is nothing like a free man charting his own destiny. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES BY MEANS OF NATURAL SELECTION, OR THE PRESERVATION OF FAVOURED RACES IN THE STRUGGLE FOR LIFE. BY CHARLES DARWIN, M.A., FELLOW OF THE ROYAL, GEOLOGICAL, LINNÆAN, ETC., SOCIETIES ; AUTHOR OF ‘JOURNAL OF RESEARCHES DURING H.M.S. BEAGLE’S [...] Read more →

Salmon and Sturgeon Caviar – Photo by Thor Salmon caviar was originated about 1910 by a fisherman in the Maritime Provinces of Siberia, and the preparation is a modification of the sturgeon caviar method (Cobb 1919). Salomon caviar has found a good market in the U.S.S.R. and other European countries where it [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

July, 16, l898 Forest and Stream Pg. 48 Tuna and Tarpon. New York, July 1.—Editor Forest and Stream: If any angler still denies the justice of my claim, as made in my article in your issue of July 2, that “the tuna is the grandest game [...] Read more →

Twinings London – photo by Elisa.rolle Is the tea in your cup genuine? The fact is, had one been living in the early 19th Century, one might occasionally encounter a counterfeit cup of tea. Food adulterations to include added poisonings and suspect substitutions were a common problem in Europe at [...] Read more →

PEACH BRANDY 2 gallons + 3 quarts boiled water 3 qts. peaches, extremely ripe 3 lemons, cut into sections 2 sm. pkgs. yeast 10 lbs. sugar 4 lbs. dark raisins Place peaches, lemons and sugar in crock. Dissolve yeast in water (must NOT be to hot). Stir thoroughly. Stir daily for 7 days. Keep [...] Read more →

Nov. 12, 1898 Forest and Stream Pg. 396 The Veterans to the Front. Ironton. O., Oct. 28.—Editor Forest and Stream: I mail you a target made here today by Messrs. E. Lawton, G. Rogers and R. S. Dupuy. Mr. Dupuy is seventy-four years old, Mr. Lawton seventy-two. Mr. Rogers [...] Read more →

Audubon started to develop a special technique for drawing birds in 1806 a Mill Grove, Pennsylvania. He perfected it during the long river trip from Cincinnati to New Orleans and in New Orleans, 1821. Home Top of [...] Read more →

From the classic British Movie, The Shooting Party, a 1985 British drama film directed by Alan Bridges based on Isabel Colegate’s 9th novel of the same name published in 1980 we find a scene set in the billiards parlor whereupon the host of the weekend shooting party Sir Randolph Nettleby walks in [...] Read more →

IT requires a far search to gather up examples of furniture really representative in this kind, and thus to gain a point of view for a prospect into the more ideal where furniture no longer is bought to look expensively useless in a boudoir, but serves everyday and commonplace need, such as [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Como dome facade – Pliny the Elder – Photo by Wolfgang Sauber Work in Progress… THE VARNISHES. Every substance may be considered as a varnish, which, when applied to the surface of a solid body, gives it a permanent lustre. Drying oil, thickened by exposure to the sun’s heat or [...] Read more →

Reprint from The Royal Collection Trust website: Kneller was born in Lubeck, studied with Rembrandt in Amsterdam and by 1676 was working in England as a fashionable portrait painter. He painted seven British monarchs (Charles II, James II, William III, Mary II, Anne, George I and George II), though his [...] Read more →